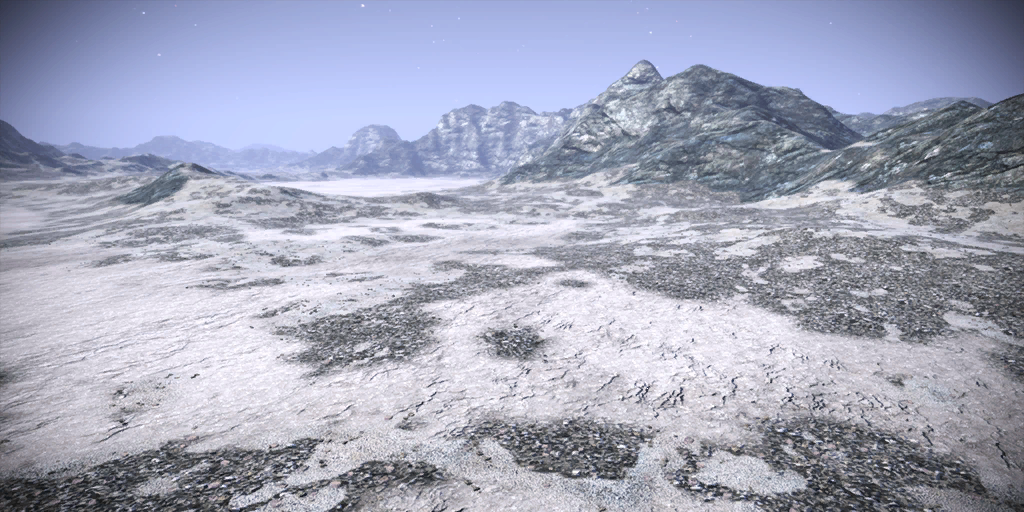

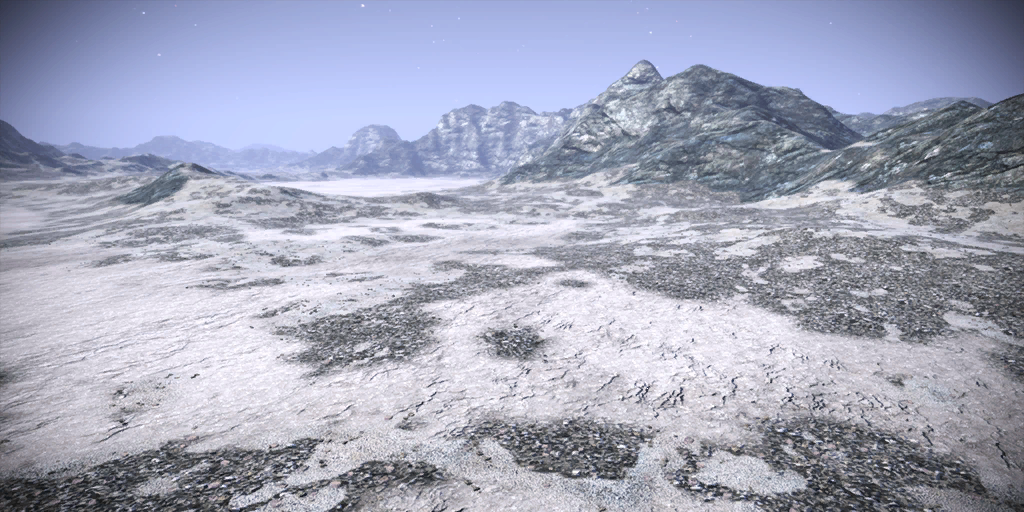

The first Mass Effect game in particular delivered to me a unique experience that no science fiction game, not even No Man's Sky, was able to reproduce. Despite being firmly in the "space opera" subgenre rather than the exploration subgenre, it was perhaps the only game where I felt like an astronaut. Mass Effect 1 is notorious for its side-quest segments where you and your teammates traverse remote planets in a ground-effect vehicle known as the M35 Mako.

|

| Raising gamers' blood pressure since 2007 or 2183. |

|

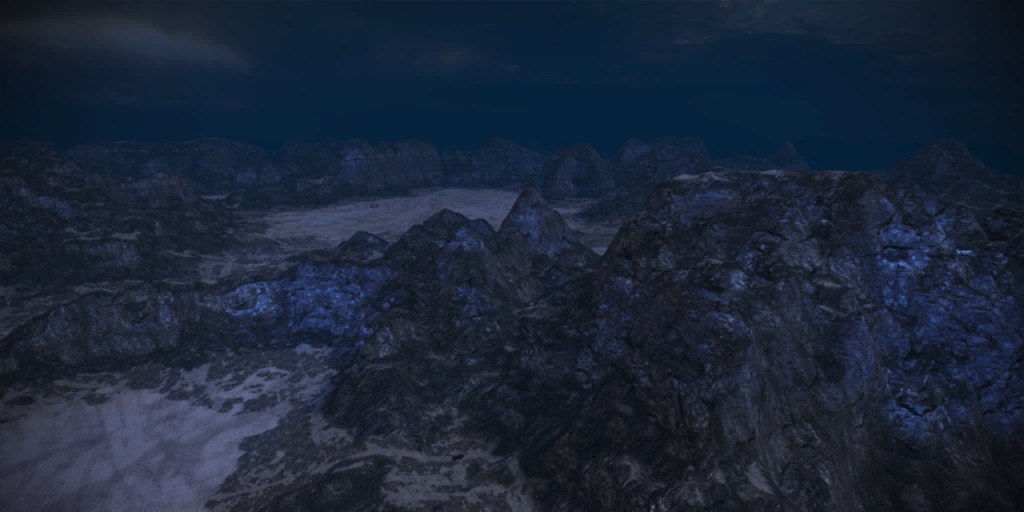

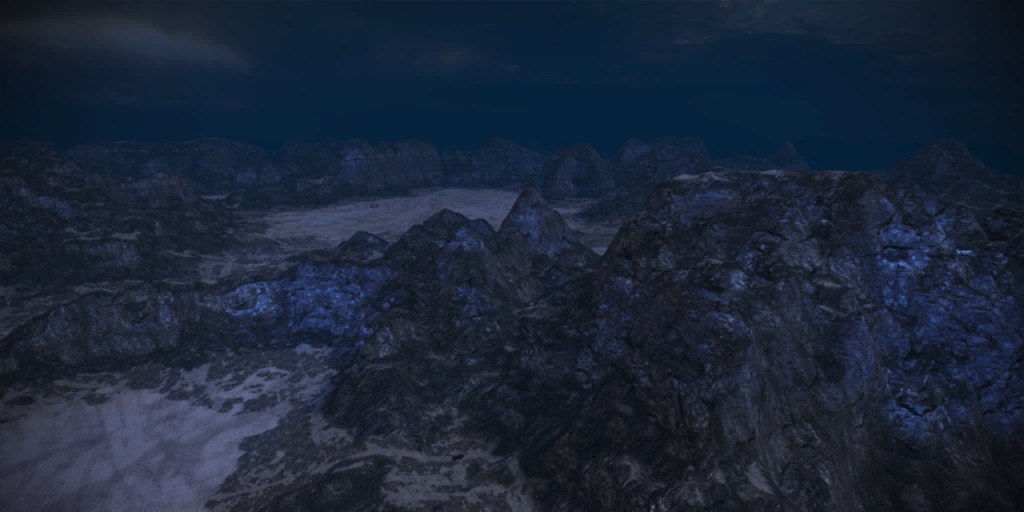

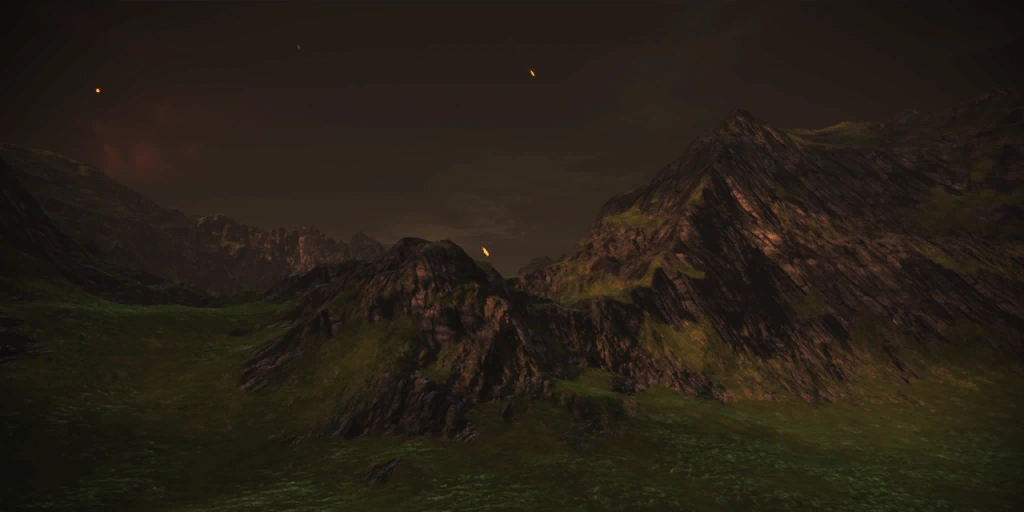

| Not pictured: the planetoid that's due to crash in a few hundred years. |

Below are a few of the in-game encyclopedia entries on some of the planets, to give an idea of what I'm talking about.

Casbin is a classic 'pre-garden' terrestrial world, with

conditions similar to

those on Earth millions of years ago. Its hot, humid atmosphere is

mainly

composed of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. An increasing amount of

the surface

is covered by simple lichen and algae. Should no unexpected

calamity occur,

these tiny planets will change the atmosphere into an Earth-like

nitrogen-oxygen

mix over the next few millennia.

Due to its potential for future habitability and sapient life,

Casbin has

been designated a Sanctuary World by the Citadel Council. Landing

is

prohibited by law, and any disturbance of the fragile young

ecosystem will

result in harsh fines and imprisonment.

At present, the planet is passing through the debris trail of a

long-period comet.

Antibaar is a cold terrestrial world with an atmosphere of methane

and argon.

Its frozen surface is mainly composed of iron with deposits of

magnesium. The

world has been noted as a possible target for long-term

terraforming; if the

atmosphere could be increased to the thickness of Earth's, the

global average

temperature would rise by 10 degree Celsius.

Antibaar's combination of low temperatures, high speed surface

winds, and low

visibility make it dangerous to explore on foot.

Agebinium is a small terrestrial world with an extremely thin

atmosphere of

carbon dioxide and krypton. Although the planet has a sufficient

mass to

maintain a thicker atmosphere, much of it has been blasted away.

The red giant Amazon is a long-period variable star, currently at

the nadir of

a 16-year cycle. At peak, its energy output doubles, lashing

Agebinium with

intense heat and radiation.

The crust is mainly composed of aluminum with deposits of tin.

Much of the

surface is coated with a fine silicate dust, which easily

penetrates the

smallest cracks to foul machinery.

Edolus is a terrestrial planet with an atmosphere of carbon

dioxide and

nitrogen. Edolus's surface is covered in wide deserts of silicate

sand, with

only a few areas of igneous rock highlands to break the abrasive,

dust-chocked

wind.

Edolus's orbit is congested with debris thrown inwards by the

gravity of the

gas giant Ontamaka. Due to a high rate of meteor impacts,

exploration is

highly dangerous.

Chohe is a terrestrial planet whose surface is mainly composed of aluminum, with numerous deposits of calcium. Though it has enough mass to retain a dense atmosphere, Chohe is nearly a vacuum. This lack of atmosphere allows a moderate average temperature, but the differences between night and day are extreme.

The surface of Chohe's sunward-facing side is usually covered by a haze of volatiles (mainly water vapor and carbon dioxide), which return to the ground as frost over the course of the long, cold night.

The Sirta Foundation has established a research outpost on Chohe to investigate the native subterranean life of Chohe, which shows incredible resilience to extremes of heat and cold.

Amaranthine is a chilly rock world with an atmosphere of carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Its frozen surface consists largely of light titanium and aluminum oxides, with deposits of thorium and other heavy metals located in the deep crust. Amaranthine was named by the human poet Sofia Cabral during her tour of duty aboard the Alliance surveyor ship Kupe. Under the dim light of the red dwarf Fortuna, the surface of this world is lit in rich twilight blues and purples even at midday.

Amaranthine is a chilly rock world with an atmosphere of carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Its frozen surface consists largely of light titanium and aluminum oxides, with deposits of thorium and other heavy metals located in the deep crust. Amaranthine was named by the human poet Sofia Cabral during her tour of duty aboard the Alliance surveyor ship Kupe. Under the dim light of the red dwarf Fortuna, the surface of this world is lit in rich twilight blues and purples even at midday.

Nodacrux is a verdant world with abundant water, temperate climate, a thick oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere and a rich ecosystem. It would seem to be perfect for life. The relatively high percentage of oxygen makes humans feel energized and alive, though it has also allowed insect analogues to grow to frightful sizes.

Nodacrux is a verdant world with abundant water, temperate climate, a thick oxygen-nitrogen atmosphere and a rich ecosystem. It would seem to be perfect for life. The relatively high percentage of oxygen makes humans feel energized and alive, though it has also allowed insect analogues to grow to frightful sizes.

Unfortunately, Nodacrux is a case of "almost but not quite." Thunderstorms are as common as on Earth, but in Nodacrux's thicker, oxygen-rich atmosphere, they are deafening and spark constant wildfires. More damning, however, are the large and ubiquitous tufts of pollen that float in the high-pressure air. In humans and other oxygen-breathing species, they cause severe or lethal allergic reactions.

Chohe is a terrestrial planet whose surface is mainly composed of aluminum, with numerous deposits of calcium. Though it has enough mass to retain a dense atmosphere, Chohe is nearly a vacuum. This lack of atmosphere allows a moderate average temperature, but the differences between night and day are extreme.

The surface of Chohe's sunward-facing side is usually covered by a haze of volatiles (mainly water vapor and carbon dioxide), which return to the ground as frost over the course of the long, cold night.

The Sirta Foundation has established a research outpost on Chohe to investigate the native subterranean life of Chohe, which shows incredible resilience to extremes of heat and cold.

Unfortunately, Nodacrux is a case of "almost but not quite." Thunderstorms are as common as on Earth, but in Nodacrux's thicker, oxygen-rich atmosphere, they are deafening and spark constant wildfires. More damning, however, are the large and ubiquitous tufts of pollen that float in the high-pressure air. In humans and other oxygen-breathing species, they cause severe or lethal allergic reactions.

On a separate topic, I know it's been a long time since I've last posted. I guess the more "novelty" you find in science fiction, the less it stands out to you. A kind of "novelty inflation." I started this blog to seek out new ideas in science fiction, and I've definitely found some.

The thing about novelty is that it shouldn't be confused for genuine quality. I think I'm done with my search for novelty, and will probably re-tool this blog to be a more general "stuff I like" blog. I'm still a fan of cool world designs and creature designs, and so those will be appearing on here. But I probably won't be restricting myself to space-based sci-fi. I've got something in mind for October and Halloween, so stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment