Mars doesn't have an active volcano system like Io, or a subsurface ocean like Europa, or hydrocarbon lakes and rivers like Titan. Mars, having a thin atmosphere, low gravity and no life, is essentially a poor man's Earth, or perhaps a poor man's Arizona. Except you can't roadtrip there with three of your college buddies.

|

| Though if you could, it would be AWESOME. (Source: NASA) |

Yet we've long had a fascination with Mars. It's one of our closest neighbors, it's where we're going next if we ever revive manned space exploration, and it's long been hoped that it harbored life at least at some point in its history. One of my favorite sci-fi novels is set there: C.S. Lewis's Out of the Silent Planet (Go read it. NOW.) Yet I think the fact that we've explored it so much removes a lot of the intrigue, and less and less are we seeing science fiction explore the Red Planet.

Waking Mars, an indie puzzle-platformer game for mobile devices (and nothing says "indie" like "puzzle-platformer for mobile") makes me a fan of Mars. For once somebody sat down thought through what an alien ecosystem might be like, and then implemented it in possibly the hardest medium: a video game. There's no combat, although you can get hurt. Your goal is to take the dormant ecosystem on Mars and...wait for it...awaken it!

|

| "Now invite them to join the United Federation of Planets." (Source) |

The game is quick to point out that these "Zoa" are not plants. Being found only underground, they do not photosynthesize. They don't produce "seeds," they produce "protocaps." The player is required to collect protocaps, plant them in fertile terrain, and collect more seeds from the new zoa. Rinse and repeat until there is sufficient biomass in the cavern for...something. Spoilers aside, the ending doesn't explain a whole lot, which is made all the worse because the game begins to drag on once you've run out of new life forms to discover. The in-game research journal is interesting, recording all the new species you find and their traits - such as diet, reproduction, vulnerabilities, reaction to stimuli. But once the rate of new discoveries starts to flag, increasing the biomass of every cavern area to Level 5 can become quite a chore, all for an alternate ending that isn't quite worth it.

Some observations:

-The Alveopyridae (aka "Harvesters") collect the biochemicals released by the other life forms in the cavern and produce electrochemical energy from them. So it's basically a literal "green energy source."

-The Bizania somehow keep gases from escaping the cavern but permit solid objects (like an astronaut) to pass through. One small question: how?!

-The Cycots are noted in the research journal as the first-ever discovered "autoapobiotic"life form; the complete organism consists of more than one autonomous biological unit. The mobile biotes collect seeds (sorry, I meant protocaps) and bring them back to the sessile biote, which looks like a nest. The sessile part eats the seeds and reproduces a new mobile unit.

-The Feranmaxis plays a vital role in the ecosystem by carrying molten magma up from below to heat the cavern. Exactly what this thing is made of that allows it to carry magma without bursting into flames is left as an exercise for the player.

Luckily, what's great about this game is that the ecosystem forms a cohesive whole. Zoa release seeds which are consumed by the motile "phyta" and the "cycots," which then reproduce, and in turn get eaten by the acidic Prax Zoa, producing more Prax protocaps, or by the Larians, producing compost which can be used to enrich the soil. Hydron Zoa seeds water the soil, enriching it, and Cephad Zoa release acidic or alkaline spores with the potential to change the pH of fertile terrain, potentially killing off existing zoa. You're not the only force at work here; sometimes you just need to give the ecosystem a nudge and it grows (or shrinks) on its own.

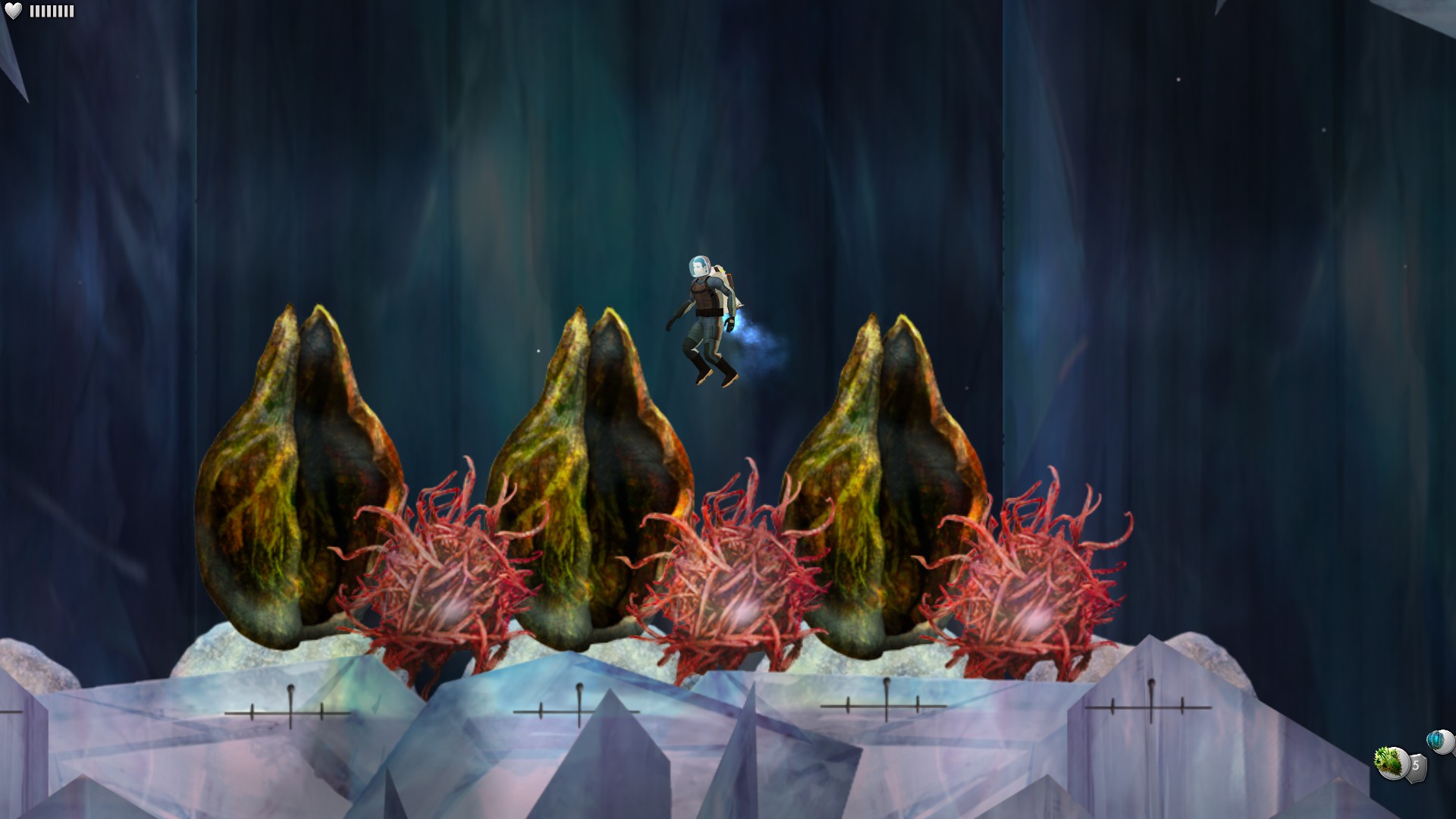

|

| Believe it or not, still on Mars. (Source) |

I'd be remiss if I didn't discuss the endgame. so just stop reading here if you absolutely must protect yourself from spoilers.

The "Sentients" (why they didn't just call them "Martians" is beyond me) and their quartz starship that you discover in the mid-to-late game didn't leave me with great memories the first time. However, on a second playthrough I realized they are also unique and interesting. They look like tumbleweeds, with no distinguishable facial features. One imagines that all those tentacles make them skilled with tools, though the limited graphical style of the game doesn't allow much detail.

Their goals seem to undermine the game, too: the surplus generated by the Harvesters is used to power their quartz starship, which launches for parts unknown in two of the three possible endings. This raises the question: are the Harvesters genetically engineered? If yes, how many of the other Martian life forms are engineered? This bothers me because genetic engineering seems like the sci-fi equivalent of "a wizard did it." In storytelling, if something's engineered it doesn't have to make sense from an evolutionary standpoint. To be fair, though, nothing is confirmed to be genetically engineered; maybe the Sentients are just really clever with the tools they've got?

|

| Strictly speaking, the research journal entry on these guys alone should be bigger than all the rest of the journal put together.(Source) |

There's no game like Waking Mars. Go play it.